Introduction

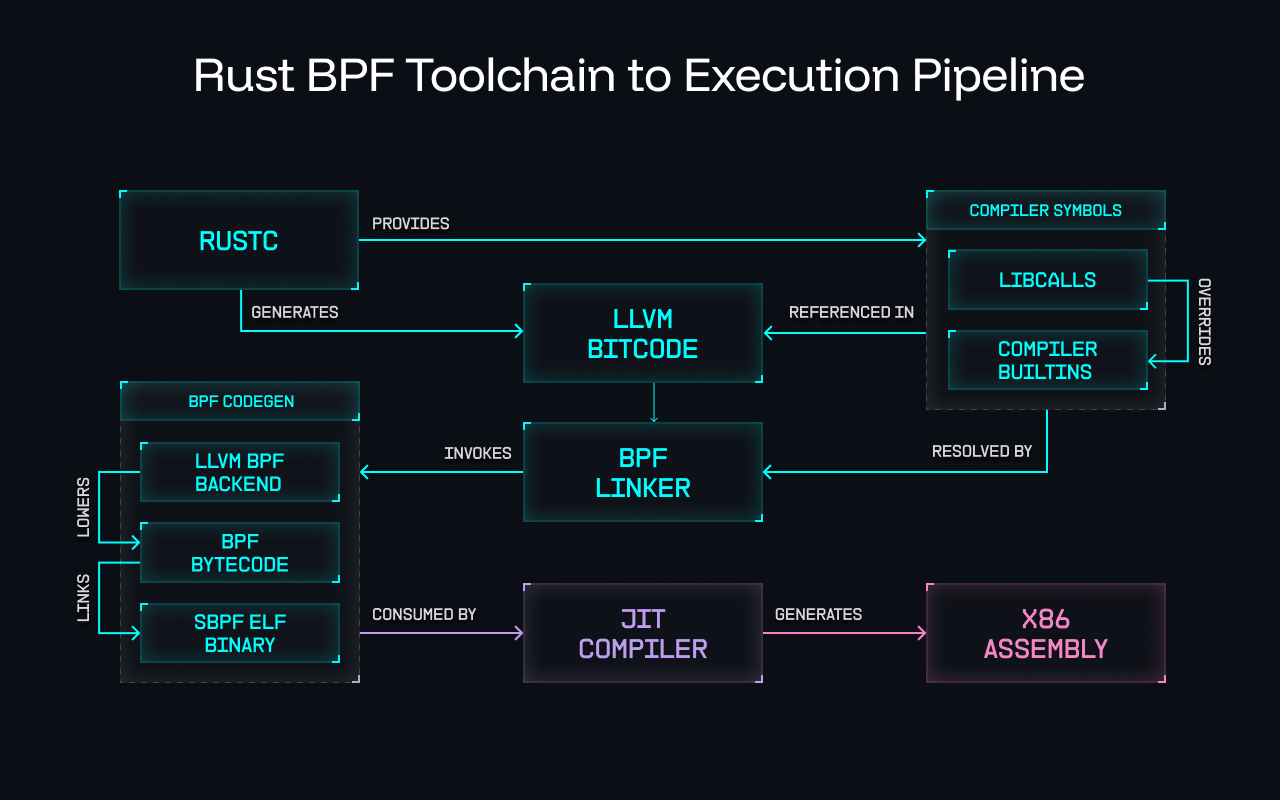

There are several fundamental differences in how the Clang and Rust LLVM frontends approach compiling and linking BPF programs. Perhaps the most significant difference is that Clang merges all available code into a single compilation unit at compile time, whereas Rust compiles each dependency crate as an independent compilation unit (For details, see our article about sbpf-linker). As a result, the mechanism used in each frontend to provide advanced functionality also diverges substantially.

When handling non-trivial low-level operations that cannot be directly lowered into machine code, the Rust compiler relies upon a mechanism called library calls (libcalls) which allows compiler engineers to provide their own custom implementations for such functionality without having to fork the entire compiler toolchain. If no custom implementation can be resolved by the linker, in some cases, as a last resort, LLVM itself will provide a generic, one-size-fits-all expansion which is not always optimal.

When compiling for BPF, Clang typically does not provide any libcalls and instead relies upon the less optimal generic LLVM expansions. By contrast, Rust provides its libcalls via compiler-builtins: A crate which includes implementations for virtually all operations that a native target might not implement natively. Importantly, it also defines all symbols as #[weak], allowing applications and libraries written in Rust to seamlessly override the default libcalls with more specialized and optimal code.

This is where the libcall model of the Rust BPF workflow offers one criminally underappreciated advantage: Rather than locking developers into hard-coded generic behaviors in LLVM, libcalls empower developers to override compiler-builtins with their own platform-specific implementations, unlocking bytecode-optimal programs without the need to fork or modify the compiler toolchain. This unlocks a level of performance and expressiveness that the monolithic LLVM approach simply cannot provide. See Rust BPF Toolchain to Execution Pipeline below for a more detailed flow of how this works:

The elephant in the room

You may be wondering: “If libcalls are powerful enough to seamlessly handle all of our platform-specific functionality without forking the compiler, why are we yet to solve for certain functionality in upstream BPF like u128 arithmetic?” Unfortunately, although the BPF backend advertises support for libcalls, there is critical compiler bug which throws an error right after libcall expansion.

As the BPF target was initially only used by Clang, which by default does not provide libcalls, there is currently a compiler bug that is triggered whenever libcalls make it into LLVM-IR. While the target supports libcalls, whenever the compiler attempts to expand them, it currently emits a (non-fatal) error. As Rust uses libcalls in compiler-builtins, this is obviously not an intended behavior. The simplest solution to this problem would be an LLVM configuration flag to optionally disable the error in libcall expansion when building from Rust. Unfortunately, in the interim, Rust BPF frameworks like Aya, and tooling like BPF linker have no choice but to ignore the error, which is not ideal.

Perplexingly, instead of simply solving the compiler bug, there is currently an open proposal to instead implement a major regression: Deprecate libcalls entirely, forcing all expansions into LLVM. Not only does this remove the flexibility to implement platform-specific functionality for userspace BPF VMs, it breaks many existing use cases and tools, and drastically raises the barrier to entry for any kind of future experimentation or optimization.

As a part of this proposal, a Rust-specific target triple has been suggested as a workaround to selectively allow libcalls for those aforementioned use cases. This confused idea fundamentally conflates frontend concerns with backend semantics. Target triples exist to describe the execution environment and ABI of the generated code — not the language or compiler frontend used to produce it. Encoding frontend-specific behavior into the target triple undermines its architectural purpose and entrenches special cases, rather than addressing the root problem.

Tapping into the power of libcalls

When a user perform a regular arithmetic operation to multiply two u128 numbers in Rust:

fn calculate_invariant(a: u128, b: u128) -> u128 { a * b }

LLVM targets that lack native u128 multiplication map this operation to a call to __multi3 – an LLVM compiler intrinsic. It is then up to the target to decide whether this gets expanded with the default LLVM implementation, or overridden by a custom libcall. If the target disallows emitting libcalls, LLVM will always fall back to its internal software expansion, inlining a large sequence of generic arithmetic instructions instead of calling the user-defined __multi3 implementation. In the context of Solana, this LLVM expansion results in some incredibly slow bytecode.

So how can we do better? You may remember the concept of JIT intrinsics introduced in our previous article where we demonstrated binding a BPF CALL_IMM instruction to a native x86 u64 wide multiplication. In the case of __multi3, not only can we extend this concept by introducing sol_multi3 – a bytecode-optimal JIT intrinsic in the Solana VM that is far more efficient than LLVM’s default software expansion – we can also demonstrate how to vertically integrate it into standard Rust u128 grammar using libcalls, all without having to disrupt the existing Clang workflow, or modify the compiler to accept our overrides.

The sol_multi3 intrinsic

To demonstrate this method, we prototyped u128 multiply support in both the Rust and BPF compilers, as well as the SVM, to show how combining custom libcalls with JIT intrinsics both drastically improve performance whilst also providing a seamless developer experience.

Here’s the Rust program we used to benchmark both approaches:

// src/lib.rs #[unsafe(no_mangle)] pub fn entrypoint(i: *mut u8) -> u64 { let mut a = unsafe { *(i as *const u128) }; let b = unsafe { *((i as *const u128).add(1)) }; for _ in 0..10000 { a = a * b; } (a >> 64) as u64 }

You’ll notice that the program doesn’t need to import any additional crates, or introduce any new grammar. It doesn’t even need to define our JIT intrinsic. It simply uses standard u128 arithmetic expressions, and either the LLVM expansion, or our libcalls will take care of the rest.

The following two programs have disassembled with sbpf for readability:

Code generated from software expansion

If we disable libcalls in the BPF backend, u128 multiply gets expanded with LLVM’s default implementation—a generic software expansion not optimized for any specific target. It works, but it’s expensive: each multiplication requires dozens of instructions, leading to 450,005 CU for 10k iterations.

entrypoint: mov64 r2, 10000 // set iteration count to 10k ldxdw r3, [r1+24] // load high and low parts of i128 for both inputs ldxdw r4, [r1+16] ldxdw r0, [r1+8] ldxdw r1, [r1+0] jmp_0028: // expensive software expansion to do u128 multiply mov64 r5, r1 lsh64 r5, 32 rsh64 r5, 32 mov64 r9, r4 lsh64 r9, 32 rsh64 r9, 32 mov64 r7, r3 mul64 r7, r1 rsh64 r1, 32 mov64 r8, r1 mul64 r8, r9 mov64 r6, r5 mul64 r6, r9 mov64 r9, r6 rsh64 r9, 32 add64 r8, r9 mov64 r9, r4 mul64 r9, r0 add64 r7, r9 mov64 r0, r8 lsh64 r0, 32 rsh64 r0, 32 mov64 r9, r4 rsh64 r9, 32 mul64 r5, r9 add64 r5, r0 mul64 r1, r9 rsh64 r8, 32 mov64 r0, r5 rsh64 r0, 32 add64 r8, r0 add64 r1, r8 mov64 r0, r1 add64 r0, r7 lsh64 r5, 32 lsh64 r6, 32 rsh64 r6, 32 or64 r6, r5 add64 r2, -1 mov64 r5, r2 lsh64 r5, 32 rsh64 r5, 32 mov64 r1, r6 jeq r5, 0, jmp_0190 ja jmp_0028 jmp_0190: exit

Code generated with intrinsic

By allowing libcalls, we can override __multi3 with our implementation that calls sol_multi3—a u128 multiply intrinsic in the SVM that takes advantage of native hardware. Since each multiplication becomes a single call instruction, this program consumes only 110,006 CU.

entrypoint: mov64 r8, 10000 // set iteration count to 10k ldxdw r6, [r1+24] // load high and low parts of i128 for both inputs ldxdw r7, [r1+16] ldxdw r2, [r1+8] ldxdw r0, [r1+0] jmp_0028: mov64 r1, r0 mov64 r3, r7 mov64 r4, r6 call -619746029 // call sol_multi3 to do u128 mul intrinsic in svm mov64 r2, r1 add64 r8, -1 mov64 r1, r8 lsh64 r1, 32 rsh64 r1, 32 jeq r1, 0, jmp_0080 ja jmp_0028 jmp_0080: mov64 r0, r2 exit

Benchmarks

CU consumption doesn’t always reflect real-world performance, so we also benchmarked both approaches in the SVM. The results confirm that the intrinsic approach is significantly faster:

bench_mul_expand ... bench: 26,365.58 ns/iter (+/- 1,937.56) bench_mul_intrinsics ... bench: 13,403.79 ns/iter (+/- 1,621.59)

Our prototype shows the intrinsic method costs ~4x fewer compute units (110k vs 450k CU) and runs ~2x faster in wall-clock time.

Conclusion

For targets like BPF and Solana, disabling libcalls would be a significant regression. The current libcall model allows developers to override functions like __multi3 with custom implementations that map directly to efficient, runtime-provided intrinsics. These intrinsics execute natively in the Solana VM, delivering far better performance and smaller bytecode than LLVM’s default software expansion.

It is our sincere hope that by highlighting the concrete and demonstrable benefits of libcalls in this article, we can rally the BPF community to converge around the obviously sensible solution for upstream LLVM – one that unlocks the full potential of libcalls without sacrificing architectural integrity.